Dismissed by some as an accidental candidate for Congress when she first ran for political office in 1987, Nancy Pelosi is one of the most powerful leaders serving the country today. Raised in a political family—her father, Thomas J. D'Alesandro Jr., was a former member of Congress and both her dad and brother served as mayor of Baltimore— she became the first female speaker of the House of Representatives in 2007.

I sat down for a chat with Speaker Pelosi in her office overlooking the National Mall during one of Congress' busiest weeks—just prior to its passage of landmark healthcare legislation. We spoke about personal beliefs, partisan politics and her hopes for America.

DONNA BRAZILE: You come from a very politically astute family, yet you didn't get the political bug until you were married with children. Tell us about your career and the influence your father had on you.

NANCY PELOSI: I didn't get the political bug to run for office myself. I don't know if I even had that until after I came to Congress—I thought I was doing my civic duty when I came. But my whole family was instilled with a responsibility for our community. Public service was a noble calling. I was born when my father was in Congress. After that he was elected mayor of Baltimore... and then my brother was mayor after him. So that was the only life we knew, helping people. We lived in the same neighborhood that my parents grew up in—Little Italy in Baltimore—and we were surrounded by people who had moved to this country. Many of them needed help and we had an opportunity to help them.

That was always part of who we were as a family. Having a political manifestation of that, that's a different thing. That was for my father and for my brother. I didn't even have the slightest interest in being a public person. But one thing led to another after my children were grown in California. And as fate would have it... [California Congresswoman] Sala Burton died.

DB: I read that when Sala Burton was getting sick, she made a point of telling you that she wanted you to run.

NP: She said, "I want to endorse you. I want you to run for this seat and I'm going to announce that I'm not going to seek reelection next year and that I'm going to support you. Will you accept my endorsement?" I responded by saying, "Sala, you'll be fine." And she said, "I know, I'm going to spend time with my grandchildren and I'll be fine." I thought, Maybe she'll change her mind, she'll run again. This was 1987, in January. She died February 1 of that year and had already made the announcement. I had no idea how sick she was and then she left us, which was very sad. And I promised her I would run, so I had to win.

DB: And what about your husband, Paul, and your five kids? How did they take it when you told them that you were running for office?

NP: Well, I didn't tell them; mostly, I asked them. Paul and I talked about it, and he said, "Do it if you want to do it." Four of my children were already in college, or else I couldn't have even considered it. The youngest, Alexandra, was going to be a senior in high school. So before I told Sala I would do it, I went to Alexandra and said, "Sala has asked me to run for her seat but it probably won't be until next year. You'll probably be in college by then." Then when Sala died, I went back to her and said, "Well now it looks as though it's going to happen now. I don't know whether I'll win, but I have a chance to run and I'm determined to win. But it would be better if it were next year because you'd be in college. I could be happy either way. If you want me to stay here with you, that's fine. If I do go to Congress I'll be here on the weekends..." And she looked at me and said, "Mother, get a life." What teenage girl doesn't want her mother out of town for a few days? It was quite a dismissal. She was kicking me out the door. She and Paul are very close so that was fine. But it was quite jarring in terms of how quickly everything happened.

DB: You came to Congress in '87, when President Reagan was still in office. Some would say it was a difficult time to help lead the country, but you came in and you figured out right away what you had to do.

NP: Everybody told me, "You will love it because you love the issues." The reason I was involved in politics was not because I enjoyed sitting at committee meetings for seven hours on a Saturday afternoon. You know that. It was because I loved the issues. I really liked it and thought, I'll stay for maybe 10 years or something like that, and then head home. I was a perfectly content person. I never had any intention to run for leadership. Not even the remotest intention or ambition. But I became motivated to do that after we lost, and then we lost and then we lost again. And I thought, You know, I don't like losing. I really don't like it at all being in the minority. And I had a plan for how we can win.

DB: Do you have any ambitions to run for the presidency?

NP: No. First of all, I have the greatest job as House speaker. I'm thrilled that we have a Democratic president—that is always important to me. I'm a little beyond that point anyway. [Laughs] One of the reasons I think I have been successful here is that I did whatever I did solidly. When I was doing appropriations, I knew my issues, I knew the policy and knew it solidly. I have to say that about myself. I really master whatever it is I set my mind to. Then, of course, that enables you, whether you plan it or not, to go to the next step. But the reason, I think, that I was able to succeed with my colleagues is they knew that whatever I was doing, whether it was whip, or leader or now speaker, was about them. It wasn't about, "One of these days I want to run for president." This is it. It's about this caucus and our success. I do think some of our leaders before—Mr. Daschle and Mr. Gephardt—were magnificent leaders, but some people thought they were running for president.

DB:I know you're quite passionate about helping ordinary people, especially in this economy. I think one issue that's important to raise is the level of partisanship in this city. Is partisan politics hurting America's progress right now?

NP: Last night as I was going through my files that I'd been meaning to go through, I was watching [a TV show about] Dolly Madison. In it they talk about when James Madison went to Congress. I mean, they were having fist fights in the House of Representatives—fist fights! And canings and everything. So passion about issues is something that is a part of ourc ountry's tradition. But let me say this: I think that people tell the story that they want to tell. Who was partisan when President Bush came to us for help to take the country from the brink of financial crisis? Our members did not like voting for the TARP bill, but they did because it was necessary for our country. It was President Bush's problem that he created with his reckless policies; it was the solution that he chose and his own party abandoned him in terms of passing legislation to pull our financial institutions from the brink. It was probably the most unpopular vote that anybody could have taken—the bailout. But who did it? The Democrats, because it was the responsible thing to do for our country. We don't like the way they began to implement it. It's better now, and we're getting our money back. So when people say that [there's too much partisanship], I think, Wait a minute, what are we talking about here? When it really mattered, when a Republican president needed something... we cooperated. We have a lot of areas where we are able to come together.

DB: Your colleagues have taken some pretty tough votes, and they're getting pounced on by the Republicans, who appear to be more popular than the Democrats right now.

NP:Well, I don't know if they're more popular. I think that nobody likes Washington, period. But they do like our positions. They just don't like that we haven't gotten it done. That's how I see it.

So when people talk about partisanship, to both parties' credit, we vote the way we believe. We have a responsibility to find our common ground. If the Republicans believe in insurance companies and protecting them, they're never going to be in support of our [healthcare]bill, which regulates insurance companies. We believe that there are market-oriented solutions but there has to be some regulation to protect the consumer.

DB: Former Secretary of State Colin Powell said that he thought President Obama had put too much before the American people in terms of healthcare legislation, financial regulatory authority and climate change. Do you agree?

NP: I love him, but I don't agree with him on this score. The fact is these are all connected. They're all about the financial well-being of our country. President Obama was dealt a terrible mess, whether it was with the financial institutions or the state of the economy; whether it was the state of the environment or the budget, distinct from the economy. And so all of these are connected. The recovery package was an immediate jolt to create jobs. The budget was a blueprint for job creation centered around climate/energy, education and healthcare. The three of them were the three pillars of recovery and job creation. They related to reducing taxes, lowering the deficit and regulatory reform. There's integrity to it, a oneness to it, that creates jobs and builds stability in the future and moves the leverage to working people instead of the elites in our country. I think that where I might agree with General Powell is that perhaps this has not been explained fully enough to the American people. This is about one thing: growing the economy of America. Healthcare is an economic issue, and a health issue, too, of course. Climate change is a national security issue but also a jobs and economic issue. Education is the source of all innovation for us, and it begins in the classroom. So, no, I think the president went out there to get done what had to get done.

DB: Given the colossal failures of the Bush administration—the wars, the economy, the reversal from budget surplus to deficit—what explains the low poll numbers for Democrats?

NP: It's because we haven't gotten the job done. And one of the reasons we haven't is because of the requirement by the Senate Republicans to have 60 votes. I put it right there at their doorstep. And if that sounds partisan, so be it. Requiring 60 votes—an extraordinary majority—on every issue that comes up, that really says, "We are going to delay." They have been very clear that they don't want anything to happen. Now, we—and particularly I, as speaker—have a responsibility to find our common ground. To look for it, to strive for it, to reach out for it. But when we don't find that common ground, we have to stand our ground and focus on why we came here. Or else why are we here, to make nice-nice to each other to make people think that we're cooperating with each other? I mean, there are big differences between our two parties in terms of who has the leverage—is it working families in our country or is it the "haves"?

DB: I read recently that you were finding common ground with Tea Partiers over a mutual distaste for special interest in Washington. How would you describe the tone and relationship between elected officials and lobbyists right now in Washington?

NP: The forces of the status quo in Washington operate in a couple of different ways. And any day that [special interest groups] can keep the status quo is money in their pocket. One tactic is to delay. That's a big operating principle for them and that's what they have tried to do with healthcare. So what we have said to them is, "Hey, public advocacy is an important part of our democracy, and people are welcome to come and make their voices heard. But when undue money weighs into the political and governmental process—there are millions and millions of dollars being lobbied to keep the status quo when it comes to health, pharmaceuticals, insurance, energy and the rest—we have to change that." Because that is not in the public's interest. That is in the special interest. The fact is, they've had it their way for a very long time and that has to change because the American people are not well served by that..

DB: What are your hopes for the future of America?

NP: My hope is that it will be a place where our children can reach their fulfillment. And they can't do that unless every child in America has the same opportunity. When I say our children, I mean all of our children. Those of us who can provide all the support and love and care for our children do them no favor by having them grow up in an atmosphere where other children are deprived of opportunity. So my goal for the 21st century is that all children and their families have the opportunity to participate in the greatness and the prosperity of America.

DB: How do you unwind after a busy week?

NP: I go to church wherever I can, as that's really important to me. That is a real renewal for me each week. On a daily basis, I indulge in a very dark chocolate candy and the New York Times crossword puzzle—an absolute must—and I read. Right now I'm reading a book about Frances Perkins, the woman behind The New Deal. The first female Cabinet member. It's just fascinating.

DB: What's on your bucket list?

NP: Oh, I'm not ready to die! [Laughs] But I would love to go to Tibet. And… first I just wanted to see my grandchildren, and now that one of them has turned 13, I say I would like to see them go to college. And anything with my dear, sweet husband. Anything he wants to do.

DB: Do you have an iPod?

NP: Oh, yes.

DB: Tell me what you're listening to. Your favorites.

NP: I'm big on U2. I have eclectic musical tastes, from the classics to rock. I usually like to keep away from the music of my children so that they don't feel like I'm intruding. But what do we have? My children, my grandchildren and us, all going to the same concerts.

Interview Copyright Capitol File Magazine.

Soucre,

click here.

And for those who lost their lives in Iraq:

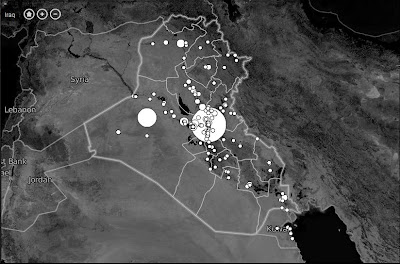

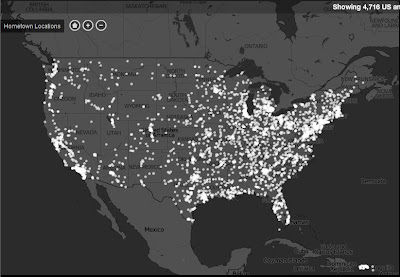

And for those who lost their lives in Iraq: There are also interactive maps of Afghanistan and Iraq that illustrate how many lives were lost in which districts/regions of the country.

There are also interactive maps of Afghanistan and Iraq that illustrate how many lives were lost in which districts/regions of the country.